Recorded talks are from Caitlin’s postdoc at the University of Oregon

In the Department of Dermatology, the Kowalski Lab has unique opportunities to collaborate with clinicians that operate speciality clinics across the state. We are interested in understanding how the skin microbiome, and microbial physiology, is altered in these unique patient populations, with a goal of developing microbial based/microbiome targeting therapeutics.

In addition to this growing area of research, and as a basic science lab, we are interested in understanding the role fungi play in maintaining the skin microbiome/skin health and uncovering the impact of the unique lipid-rich skin niche on microbial ecology and physiology (see below).

Resident fungi as gatekeepers of skin health

Human skin is uniquely dominated by the genus of yeast-like fungi called Malassezia that belong to the phylum Basidiomycota making them distant relatives to dominant fungal colonizers of the human gut (i.e. Candida species, phylum Ascomycota). Even though Malassezia are thought to be ubiquitous skin colonizers of not only humans but mammals in general, we know relatively little about their biology, how they are skin-adapted, how they contribute to skin microbiome stability and composition, and how they shape skin and overall host health.

While Malassezia colonizes most people asymptomatically, and can potentially provide benefits to the host (see below), there are instances where Malassezia is known to (or suspected to) contribute to skin pathologies that dramatically impact patient quality of life. These include seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor, folliculitis, and to a less clear extent, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. In immune compromised patients and neonates receiving parenteral nutrition, Malassezia can also cause uncommon but serious bloodstream infections.

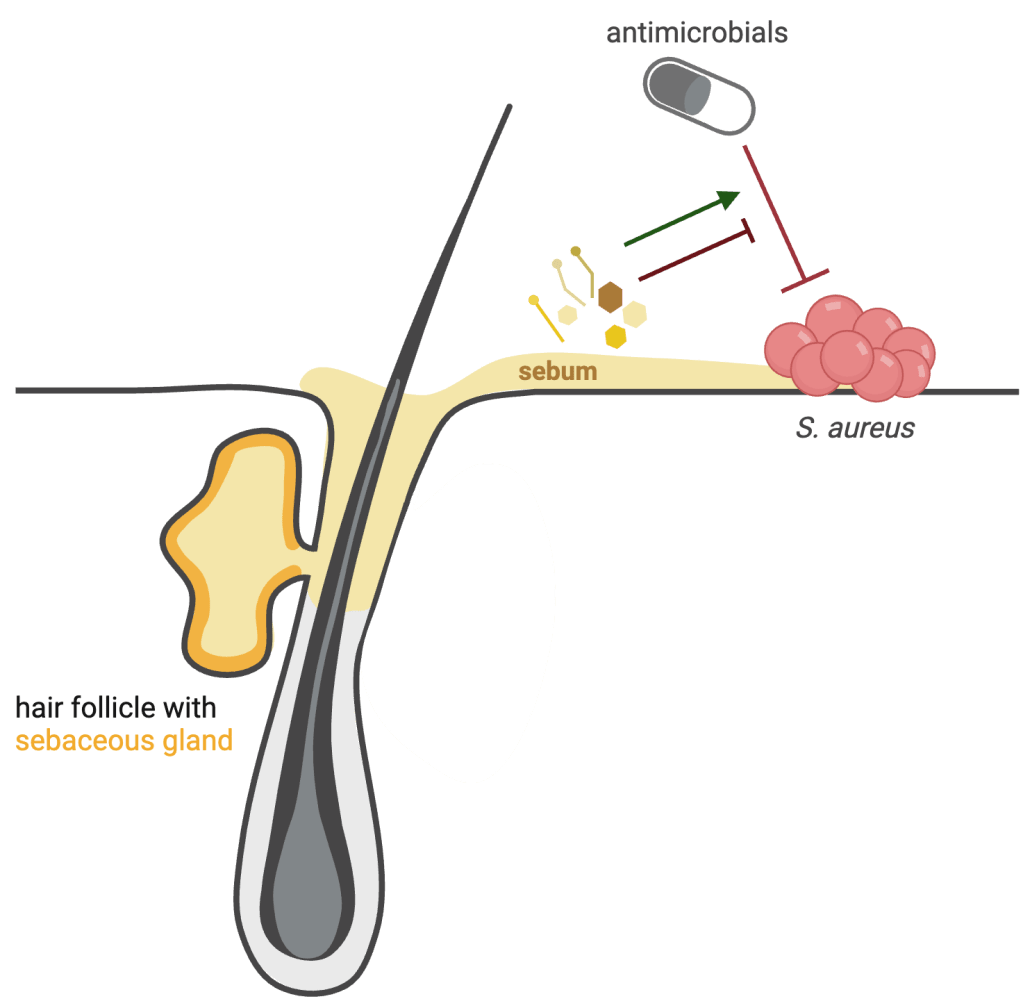

One way that the microbiome contributes to host health is by inhibiting the invasion or expansion of pathogens, called Colonization Resistance. This has been a major focus in the skin microbiome field, as labs around the world are searching for new antibiotics to treat drug-resistant skin pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus. For my postdoc work, I wanted to better understand how skin-resident fungi like Malassezia might contribute to colonization resistance, since most groups have focused specifically on bacteria-bacteria interactions. I went on to identify a potent antimicrobial produced by a Malassezia species that is uniquely active within a skin-like environment. The compound, 10-hydroxy palmitic acid (10-HP) is bactericidal against multi-drug resistant S. aureus strains in permissive conditions. In contrast, many staphylococci that are residents of human skin are unaffected by 10-HP. This manuscript was published in Current Biology in April 2025. UO News did a nice media piece about our Current Biology paper, located here. This work raises many interesting questions that my lab will investigate:

- How do fungal products, like 10-HP, impact bacterial sensitivity to skin-relevant stressors and antibiotics? Why are skin resident staphylococci less sensitive to 10-HP and other antimicrobial fatty acids?

- How do Malassezia generate 10-HP if they cannot synthesize fatty acids de novo? Can exogenous lipid sources support 10-HP production on skin? Do certain environmental cues control 10-HP production by Malassezia (i.e. cell density, oxygen, pH, etc.)?

- Do different species of Malassezia generate 10-HP or different hydroxy fatty acids that have bioactive functions? How do the lipids provided to support Malassezia growth impact its interactions with the host or other microbes?

- Does 10-HP production by Malassezia impact it’s interactions with other Malassezia species that might share the same niche? Why would it produce 10-HP if the first place? Does generation of 10-HP impact other lipophilic microbes on the skin?

- How, in a spatial sense, do Malassezia colonize skin? How does this spatial structure change during overgrowth/disease? How are Malassezia transmitted both across an individual body but also between people? Are there phenotypic distinctions between Malassezia from healthy skin and those isolated from cases of disease (i.e. seborrheic dermatitis)?

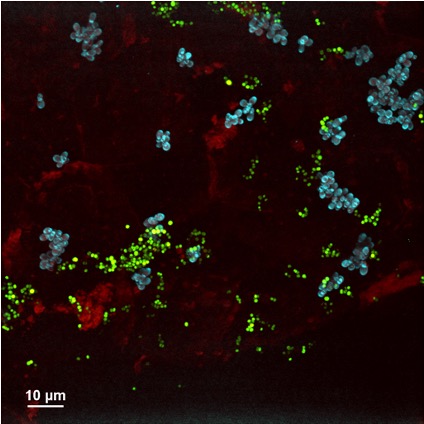

- With new, and improving, genetic approaches to study Malassezia can we better understand the genes and pathways the regulate phenotypes to determine their contributions to skin colonization, impacts on the microbiome, and communication with the host? For example, some Malassezia species auto-aggregate in culture and on mammalian skin, is this aggregation important for surviving in the harsh skin niche? Which genes control and mediate adhesion? Could these be targeted in cases when Malassezia overgrowth impacts the skin barrier and patient quality of life (i.e. seborrheic dermatitis)?

Skin lipids as mediators of microbiome homeostasis and skin health

Human skin is incredibly lipid rich, with some estimates stating that lipids account for up to 25% of the total mass of the stratum corneum (the outer most layer of the skin). In addition to the lipids that contribute to the skin structure, sebum is a lipid-rich substance that is extruded onto the skin surface by sebaceous glands. This abundance of lipids supports the growth of many skin-resident lipophilic (lipid loving) and lipid-dependent (lipid requiring) microorganisms that further breakdown, modify, and thus diversify the lipid pool.

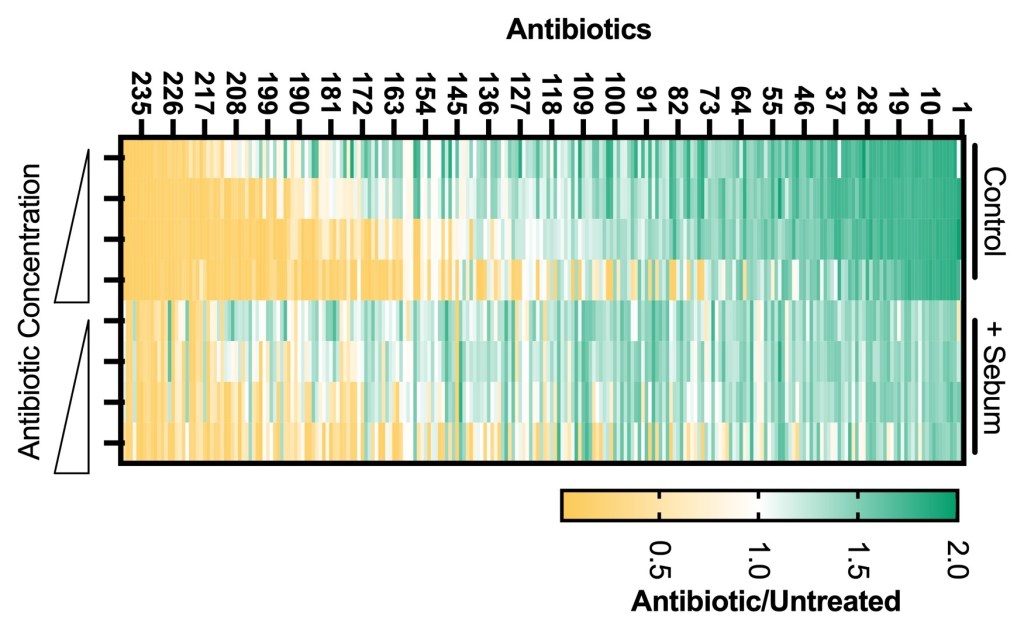

Heat map depicts S. aureus sensitivity to 240 antimicrobials in standard (control) conditions or with the addition of synthetic sebum (+sebum). Yellow indicates compounds that reduce S. aureus growth, green indicates compounds that enhance S. aureus growth. This work was the focus of Dante’ James’ (now UW Madison) UO undergraduate thesis.

How do host and microbial lipids on the skin impact the skin barrier, host-microbe interactions, and microbe-microbe interactions? Despite the abundance of lipids in this niche, many colonization resistance screens are performed in the absence of lipids possibly overlooking the existence of important lipid mediators that control microbial growth. We are interested in understanding how microbes process and transform the skin lipid pool (including lipids from the host, other microbes, and even xenobiotic sources) and what the consequences are for microbe-microbe and host-microbe interactions.

We are also interested in how sebum components, that includes lipids and other small molecules, impact microbial physiology and sensitivity to antimicrobials. This project began at the University of Oregon, where we were interested in understanding how sebum lipids impact S. aureus sensitivity to diverse antimicrobials (heat map, left). On most healthy skin sites, S. aureus colonization is typically transient but is also a risk factor for systemic infection. Some skin diseases like atopic dermatitis/eczema result in stable S. aureus skin colonization that is treated with a combination of antiseptics and antibiotics. Thus understanding how the skin environment impacts S. aureus antimicrobial sensitivity is an important consideration.

- Can we identify microbial lipid mediators of colonization resistance? Are there lipid products that support the growth of complex skin communities? When features of the skin environment change during disease (i.e. change in pH, change in lipid substrates) how does this impact the inter-microbial interactions?

- Sebum is produced by holocrine secretion, meaning the sebocytes rupture releasing the entire cell contents which includes the large supply of lipids but also other small hydrophobic molecules such as hormones. Do these hormones alter the physiology of the bacteria that reside within the hair follicles where sebum is highly concentrated (i.e. Cutibacterium or Malassezia?).

- How do skin relevant lipids alter S. aureus sensitivity to antimicrobials? Following up on hits from the screen performed at UO, we are intersted in understanding how lipids are altering sensitivity to diverse classes of antimicrobials? Is there one component that plays a role, or is a lipid mixture critical for altering S. aureus physiology?